|

General Directions for Academic Writing |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contents: Introduction

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

This lesson offers some general guidelines for writing a successful academic paper. There are a few "rules of thumb" which will guide you through most of the various types of writing you will be asked to do for school. Your topic for this assignment will be to discuss the problems associated with attending high school (not home school). Discuss the problems involved with attending regular (not home school) high school. THE RHETORICAL SQUARE will help you answer the very first questions about your assignment.

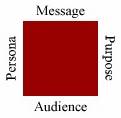

The purpose of the square is to help you identify important parts of your essay. You will want to identify your message, your purpose, your persona, and your audience. For example, if you are writing about slavery, your message might be, “people should think about whether any individual ought to be forced to act entirely against their will”; your purpose might be to get people to understand that slavery is wrong; your persona might be a serious thinker (you don’t want to come across as foolish or naïve), and your audience might be your classmates, the state you live in – even the whole world! The construction of your essay will rely upon your decisions about these four things. Now, draw your own square so that it’s big enough to write in, and fill in your square. Answer the questions posed by the square as you see fit. You can only procrastinate so long (although even when you procrastinate, your unconscious mind is at work). Don't let the project go "cold" by putting it on the back burner. Once you begin, it will take on an energy of its own, but you have to begin it. The first step to great writing is to brainstorm. The following links offer great brainstorming activities. Link: http://www.graphic.org/goindex.html You may wish to do any or all of the activities listed below to get yourself started. • Use a graphic organizer --a cluster, a flow chart, a Venn diagram, a T-graph --whatever best suits the information you will be organizing. • Use the bullets on your word processing program to separate your thoughts. • Use free-form sketching to jog your brain and locate your focus. • Make a list of questions you have about your subject. • Talk to others and record what they say about your topic. Brainstorm using one of the organizing principles above. It doesn't matter how you do your brainstorming as long as you do it. Don't skip this step, because it is a relatively painless way to get you creative juices flowing. It doesn't matter what kind of paper you are trying to spin, you must have a magnetic center to your writing, a hub around which your details revolve. The thesis or center point in your paper is its organizing principle; it keeps your thoughts from wandering too far from the point you wish to make. A thesis gives you something to prove or show, as it provides the basis for your argument. All writing springs from ideas. So start your writing with a sound thesis and you will, more than likely, write a sound paper. Link: http://owl.english.purdue.edu/handouts/general/gl_thesis.html Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/thesis.html Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/thesis.html#assigned Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/thesis.html#unassigned Not all theses are created equal. How do you know when you have it just right? Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/thesis.html#strongthesis Write your thesis statement. You may need to write it several times before you are satisfied. You don't have to use standard outline form if it feels too constrictive, but make some kind of outline to guide you through your writing process and keep you on track. An outline is like a road map: it provides you with the main arterials to your destination and tells you where and which way to turn. You can't get lost if you have a solid outline to follow. One of the most important organizational skills you can acquire as a writer is the ability to relate categories to details. You are probably already skilled at doing this and just need to raise your awareness of how to apply the skill to organizing an effective piece of writing. Your outline will provide the categories for supporting your thesis that will be components or elements of your thesis. The details under each category will provide the evidence or support for whatever point(s) you are making in your paper. Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/outlines.html Begin your outline by listing some of the main points you wish to raise in your paper. Don't worry about their order just yet. Get them down first. Then you may rearrange at will. Once you have arranged your ideas in what seems to be the best order (you can always change your mind later), begin supplying the details which seem likely to support each category. Depending upon what kind and length of paper you are writing, you will need just a few or a great many details. Go ahead and make an outline. The purpose of your introductory paragraph is to tell your reader where your paper is headed, what point or points you plan to make, what subject you will explore. In any kind of expository prose (non-fiction, not narrative) your thesis statement will reside in this paragraph, usually at the very beginning or the very end of the paragraph. Remembering that your introductory paragraph contains your main idea or thesis statement, usually at the end, you should be prepared to re-write this paragraph more than once. Ask yourself, as you read over your work, does this introduction grab the reader's interest? Is it clear? Have you been able to cultivate a voice which is your own? Then, revise, mess around with it and see what you come up with. Link: http://www.rscc.cc.tn.us/owl&writingcenter/OWL/HowtoBegin.html#Introduction Link(specifically for research papers, but good stuff generally): http://owl.english.purdue.edu/workshops/hypertext/ResearchW/writeintro.html In most academic writing, this involves presenting evidence in the forms of facts, statistics, quotations or literary references which bolster and support your thesis. You may gather your support from a variety of sources, depending upon the type of paper you are writing. In an essay about a work of literature, for example, your evidence will be in the form of either a quotation or a direct reference to what has taken place in the literary piece. In a research paper, your support will come from the sources you have read. Your job in a research paper is to state your thesis and then synthesize the works of others, sometimes quoting directly, sometimes not, to support your ideas (giving credit to the original sources, of course). In a more personal reflection essay, you may draw on your own experiences. All of this counts as evidence or support for your thesis. Link: http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/evidence.html Conclusion paragraphs run the risk of being dull and repetitive in student writing. Why? Because students are often instructed to restate their thesis and summarize their proofs in their conclusion paragraph. And they do just that, parroting what they have already said, mechanically, without interest or passion. It is a waste of your talents and efforts to leave your reader with a flat and stale ending. Your conclusion paragraph is your last opportunity to win your reader over to your point. Any good piece of writing should provoke the reader into new thoughts or attitudes. Great writing should transport readers into a new world of perception, like a train which picks you up in one part of the universe and drops you off in another. Don't waste your conclusion paragraph on banalities. While it's fine to nail down your point in your conclusion paragraph, remember to throw in a little "food for thought" too. Link(more specifically for essay/literature): http://web.uvic.ca/wguide/Pages/EssayWritingConclusions.html Link(good all-around): http://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/conclude.html Don't forget to proofread! It would be a shame to write a quality essay and turn it in with grammatical mistakes. Look over the list of common errors below, and be sure you haven't made any of them. A Note on PlagiarismIt is always tempting, when writing an academic paper, to use the thoughts of others who are more knowledgeable or talented than you feel yourself to be in your work. Some writing, such as research papers or persuasive essays that rely upon research to make their points, must incorporate the words and/or ideas of others into their text. For such instances, there is a citation process that allows students to give credit for information used to the original source. With the advent of the Internet as a reference and research tool, and students’ familiarity with the copying and pasting process, teachers have been forced to confront more and more students on issues of plagiarism. Because Laurel Springs encourages independent thinking and creativity, the problem of plagiarism is of particular concern to our teachers. Students may not always realize that, even when an original source is not quoted word-for-word, there must be a citation crediting the source. Let’s look at a definition of plagiarism. Plagiarism:To use and pass off the ideas or writings of another as one's own. To appropriate for use as one's own passages or ideas from another. To put forth as original to oneself the ideas or words of another.

What does this mean to you? It means that if you do some reading or research to create a project or essay of your own, you need to cite the sources for your ideas even if you don’t quote directly from the original source. The Modern Language Association (MLA) has prescribed formats for citing references. There are choices as to how you handle your citations, depending upon the nature of your paper. Check out the different types of citations by clicking at the bottom of the link page. http://www.hcc.hawaii.edu/education/hcc/library/mlahcc.html If you are writing a persuasive or interpretive essay, you have some choices as to how you cite references, depending upon how you are presenting information. The important thing is that you give credit where credit is due! http://www.indiana.edu/%7Ewts/wts/evidence.html#citing When you are responding to one particular text (such as a novel) that you share with your teacher, you may use internal citations, giving only the page number, if the title and edition of the text are the same for you and your reader. In short, whenever you are dealing with information that you are writing down, you need to cite references for exact words or ideas or statistics that you include. If you don’t, you are plagiarizing. Once you have completed your essay, don't forget to proofread! It would be a shame to write a quality essay and turn it in with grammatical mistakes. Look over the list of common errors below, and be sure you haven't made any of them. The Handy-Dandy Tricky Word ReferenceThe following words often give people trouble. When in doubt, consult this table.

copyright 2003 Synva Mintz and Laurel Springs School. Not to be used without permission. |