The Decline of the Papacy

Papal Palace, Avignon, France

In 1305, through the influence of Philip IV, king of France, the papal court was moved from Rome to Avignon. This period when the popes were dominated by the French monarchs has become known as the Babylonian The Late Middle Ages saw religious conflicts as well. The papacy again became involved in a power struggle with kings.aptivity. The papal palace today remains a symbol of this period of exile.

At the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century, Pope Boniface VIII opposed the kings of France and England. He did not want them to impose taxes on clerics, nor did he want French king Philip IV to try a French bishop in a royal court. Boniface's opposition backfired, however. Kings had become so powerful by the Late Middle Ages that they could assert their rule over everyone within their borders.

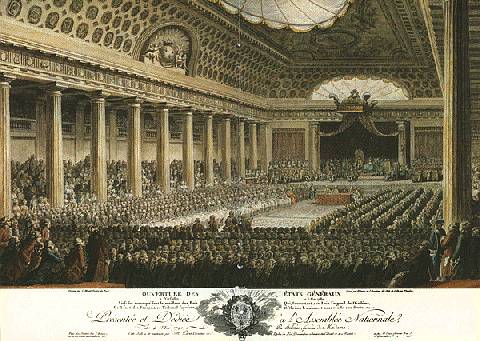

In 1302 Philip IV called a meeting of

the three estates, or classes, of his kingdom: nobles, clerics, and commoners.

This meeting supported the king and condemned the pope, showing how a

representative institution could serve the interests of the king. The meeting

was the beginning of the Estates-General, the first representative body in

France.

Estates-General, the first representative body in France

Faced with opposition from all classes of French society, Boniface backed down. Soon after, the papacy moved from Rome to Avignon, a city close to the French border. The next several popes were Frenchmen, and many people began to think that the papacy had become subordinate to France. Papal prestige plummeted as a result, and the papacy was never able to recover fully.

The Great Schism

The popes remained in Avignon from

1309 until 1378. Some Europeans called it the Babylonian Captivity, recalling

the biblical story of the Jews who were taken from Israel to work as slaves for

the Babylonians. Many Christians longed for the pope to return to Rome. Instead,

in 1378, they got two popes, one ruling from Avignon and the other from Rome.

This scandal, called the Great Schism of rival popes, was made even worse when a

third pope was chosen in 1409. The other two did not step down, and so three

popes claimed to be head of the church. The schism finally ended in 1417 with

the Council of Constance. The council deposed all three popes and elected Martin

V, who made Rome his headquarters.

Growing Discontent

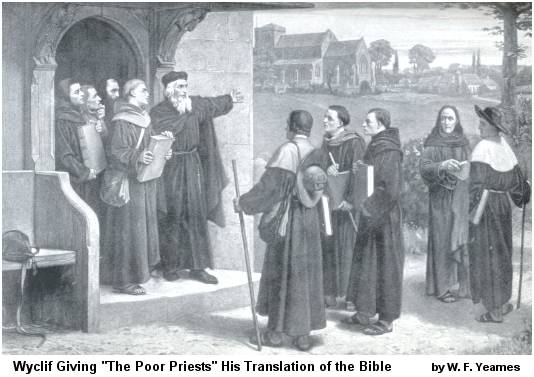

John Wycliffe Trained in the scholasticism of the medieval Roman Catholic church, 14th-century theologian John Wycliffe became disillusioned with ecclesiastical abuses. He challenged the church’s spiritual authority and sponsored the translation of the Christian Scriptures into English. Here, Wycliffe is pictured reading his translation of the Bible to English nobleman John of Gaunt, far right. Wycliffe’s writings later inspired leaders of the Protestant Reformation such as John Huss and Martin Luther.

Some people were discontented not just with the papacy but also with the church and its teachings as a whole. Englishman John Wycliffe, a professor at the University of Oxford, taught that popes and clerics did not make up the church. Instead, Wycliffe claimed that the church was the community of all believers. Wycliffe believed that salvation came through study of the Bible, not through the rituals of priests and bishops. According to him, the king, not the pope, should control church reform.

Wycliffe's ideas were extremely popular in England. Some of the peasants in the revolt of 1381 were influenced by him. He had support among the nobles as well, and even many priests adopted his views. Although Wycliffe was not persecuted during his lifetime, his supporters, called Lollards, were condemned as heretics after his death. Many were killed, but others survived, and Lollardy continued into the 16th century.

Some of Wycliffe's ideas also became

popular among Czechs in Bohemia. Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman Empire, and

it grew rich during the 14th century. It too was hit by famine and plague, and

many Czechs revolted under the pressures of hardship. Their protests were

largely religious.

Led

by religious reformer John Huss, they demanded changes in the church, focusing

on the part of the Mass called communion, which involved the ritual consumption

of the body and blood of Christ in the form of bread and wine. Over the years,

priests had come to take communion in both forms, but ordinary believers were

only allowed the bread. Huss’s followers, called Hussites, insisted that

everyone be allowed to take communion in both bread and wine. This was more than

an argument over ritual—it was a demand for equality. Huss was burned at the

stake in 1415 and a civil war broke out in Bohemia. Huss’s followers were

defeated in 1436, but their demand for communion in both forms was granted.

Led

by religious reformer John Huss, they demanded changes in the church, focusing

on the part of the Mass called communion, which involved the ritual consumption

of the body and blood of Christ in the form of bread and wine. Over the years,

priests had come to take communion in both forms, but ordinary believers were

only allowed the bread. Huss’s followers, called Hussites, insisted that

everyone be allowed to take communion in both bread and wine. This was more than

an argument over ritual—it was a demand for equality. Huss was burned at the

stake in 1415 and a civil war broke out in Bohemia. Huss’s followers were

defeated in 1436, but their demand for communion in both forms was granted.