Diderot

Diderot

The Age of Enlightenment (also

called the Age of Reason) in Europe began in the 1600’s and reached its height

during the early to mid-1700’s. It brought together the ideas of the Renaissance

and the Scientific Revolution.

Before the Renaissance, scholars felt

that life on earth was not worth very much, and the task of mankind was to

devote itself to preparing for what they believed would come after death - life

in a wonderful, heavenly place. They believed that life began only after death,

and that focusing on the enjoyment of earthly life was sinful.

Until the

1500’s, western Europeans generally saw the world in one of several ways. Many

believed it was best to rely on faith, and most truths were beyond the

understanding of the common people. If one simply lived obediently by the rules

of the church, without questioning its authority, that would be enough. Some

scholars had learned to use reason to explain their observations, and relied on

this rather than church teachings - but this was fairly new. Most people thought

everything in nature and society was connected, and that they were like parts of

a living thing, which therefore couldn’t be changed. Society was seen to be like

a tree - with the peasants at the roots, the clergy and merchants in the lower

branches, and the nobles at the very top. This perspective helped to strengthen

rigid social classes, and it was considered natural that some people would be

poor and powerless, some rich and powerful. While this may seem very oppressive

to us today, at that time it gave people the feeling they had their own

particular place in the world, and they understood what was expected of them.

Most people didn’t question it.

These ideas began to change during the

years of the Renaissance. Followers of a philosophy called “humanism” emphasized

the importance of human beings and their particular place in the universe.

Humanism taught that every person has dignity and value, and emotions and

personalities are important and should be respected. They believed people can

improve their lives by understanding the world and changing it. The value

humanists placed on earthly life opened up a great deal of interest in learning

and developing the arts. All kinds of art, education, and scientific inquiry

thrived during the Renaissance. European explorers were traveling to different

cultures and bringing back new perspectives, new inventions, new ideas. People

began to believe that progress could be a good thing.

The Scientific Revolution is a term

used for a point of view that became popular at the end of the Renaissance. It

taught that the only way to really understand life is through science, not as

had previously been thought, through religion. Nicolaus Copernicus, Andreas

Vesalius, Galileo, Johannes Kepler, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton were among

the scientists during this period who made important contributions to the

scientific understanding of the laws of nature. They and other scholars studied

scientific writings from earlier centuries, and began taking a closer look at

the natural world around them. Their observations and experiments led to new

thought concerning the importance and relevance of science. The scientists of

the Renaissance made many discoveries that changed people’s ideas about how the

world works.

The work of these scientists paved the way for what is called the Age of Enlightenment, when philosophers tried to apply scientific reasoning to all aspects of life. During the Age of Enlightenment, philosophers believed that happiness didn’t come from devoting one’s life to God, as was previously thought, but from following a set of natural laws which would result in greater freedom for mankind. These philosophers and scientists saw the universe as a sort of machine, which was set in motion by its creator, then left alone to run by the laws that were designed to keep it going. They believed the only way to understand anything was by reason, not by faith.

The leading thinkers of the

Enlightenment were called philosophes, which means philosophers in French. The

philosophes didn’t agree with each other on everything, but there were certain

themes that appeared over and over in their writings.

Scholars during

the Age of Enlightenment, or Reason said humans have an important advantage over

animals because of their ability to reason. They said animals were only able to

act from their emotions and instincts, but humans were able to make decisions by

using their minds, and act by their own force of will rather than from their

feelings. “Knowledge is power,” was the key idea during the Enlightenment.

Freedom of thought was considered to be crucial. The philosophes said

that because humans are capable of reason, they should challenge anything

smacking of ignorance or superstition, and carefully question traditional

authorities - especially Christian theology. In the words of Immanual Kant, “The

motto of the Enlightenment is ‘Dare to Know! Have the courage to use your own

intelligence!’”

Human progress was a common theme

in the writings of the philosophes. They believed that the “golden age” was

ahead, not to be found by studying Greek philosophers and other thinkers of the

past. Part of the idea of human progress involved humanitarianism, or a belief

in the importance of improving people’s daily lives. Easing human suffering was

seen as a worthy goal, and the thinkers of the Enlightenment spoke out against

religious persecution, slavery, and oppression of all kinds.

Thomas

Hobbes, an Englishman in the 1600’s, believed people are basically wicked and

selfish, and they need a strict ruler to keep them in order. This was in a time

when most of the countries of Europe were strictly ruled by very powerful kings

and queens, and many political thinkers were promoting ideas of freedom and

liberty. He said people had no right to rebel, because if they were left to

themselves, they would destroy themselves. Hobbes thought that without an

all-powerful government, people’s lives would be “poor, nasty, brutish, and

short,” because people were basically driven by fear of each other and a desire

for power, and therefore needed to be controlled. Without control, human society

would simply be “a war of all against all.”

In direct opposition to these beliefs

were the ideas of John Locke. John Locke was an English philosopher who said

people have a right to life, liberty, and property. He said this was a “natural”

right because humans are born free and equal. Locke believed people were

reasonable beings, and had a natural ability to govern themselves and work for

the welfare of the whole society. In his mind, government should be a sort of

contract between the people and their rulers, in which the rulers promise to

protect the natural rights of the people. He encouraged rebellion against an

oppressive government that abused these basic rights.

Several other

philosophers also had an important impact on thinking during the Enlightenment

years. René Descartes was a French philosopher and mathematician who fiercely

believed in questioning everything and vowed “never to accept anything for true

which I did not clearly know to be such.” He said nothing should be accepted on

faith, and everything should be doubted until it could be proved by reason. He

knew himself to be a thinking, doubting, questioning person, and therefore he

knew he existed. He is well known for his statement,

“I think, therefore I am.”

Voltaire (born as Francois Marie Arouet) was

a popular writer who had strong political and philosophical opinions, especially

concerning religious intolerance and anything else that interfered with the

rights of individuals. He hated intolerance and injustice of any kind, and

wrote, “I shall not cease to preach tolerance from the rooftops as long as

persecution does not cease.” In defense of free speech, Voltaire is thought to

have said, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your

right to say it.”

In the 1700’s, wealthy families often displayed scientific instruments in their homes, just as people today display works of art or other things that are important to them. Telescopes and microscopes were primitive then, compared with what we have today, but guests were often invited to look through them, to see the night sky or to observe some tiny thing of interest, such as the wing of a butterfly.

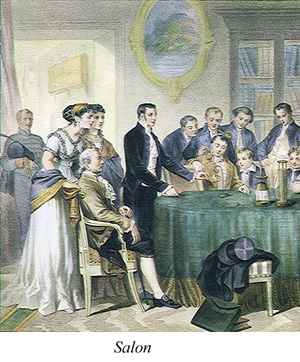

Originating in Paris, it became

fashionable in Europe for wealthy hostesses to invite poets, musicians,

philosophers, and other interesting conversationalists to their homes for social

gatherings called salons. These salons became intellectual centers where great

artists, writers, and scientists would gather each week to share ideas. It was

still generally believed that women were not as capable as men, and they

couldn’t make real contributions in the arts and sciences - but the women who

conducted salons achieved prominence by providing an important forum for the

exchange of ideas. The salons came to be considered so important that Catherine

the Great, of Russia, paid someone to attend them regularly and report back to

her about what had been said.

The ideas of the

Enlightenment played a significant role in some of the events that followed.

These years introduced ideas of liberty and freedom that had never really been

considered before. Later this year you will learn about two revolutions that

took place partly as a result of the questioning and arguing that began in the

salons of Europe.

Enlightened despots no longer

justified their absolute power by saying they had “divine right” to rule, but

identified themselves as being “servants of the state.” Frederick the Great of

Prussia, Catherine the Great of Russia, Maria Theresa and her son, Joseph II, of

Austria, were all enlightened despots. They built roads and bridges, increased

religious tolerance, sometimes conducted experiments, learned to play musical

instruments, and wrote poetry.

A French philosophe named Denis Diderot

spent almost twenty-five years working with twenty other men to compile all the

knowledge of the world in one place. Of course, it wasn’t really all the

knowledge of the whole world. It was a huge collection of articles on

literature, religion, government, science, technology, representing the bulk of

everything known about the sciences, technology, and history at that time. This

great work was called the Encyclopédie. It took twenty-one years to get all 35

volumes printed and published.

Diderot wanted to

show people all the wonders of modern reasoning and scientific thought. The

Encyclopédie showed beautiful, detailed illustrations of the latest machines of

the day, surgical techniques, birds and animals from newly explored continents,

drawings that showed the step-by-step construction of a tennis racket, and many

other amazing things which expanded the public’s view of the world. It also

contained articles criticizing the government and the Catholic church, and

preached religious tolerance.

The following excerpt from

the Encyclopedie shows some of the political views held during the

Enlightenment:

“No man has received from

nature the right to rule others. Liberty is a gift of heaven and each individual

of the same species has the right to enjoy is at soon as he enjoys reason. If

nature has established any authority, it is paternal power, but paternal power

has its limits, and in the state of nature it would end as soon as children were

in a position of self-dependence. All other authority originates in something

other than nature. Close examination will show that it derives from one of two

sources, either the force and violence of those who take possession of it, or

the consent of those who have submitted to it through a contract made or assumed

between them and whoever they have vested with authority.”

Because of

such statements, Diderot and some of the other men who worked on this massive

enterprise went to prison. But the Encyclopédie was read by many, and its ideas

spread through Europe. Before long, English and Scottish writers, inspired by

Diderot’s accomplishment, produced the first Encyclopedia Britannica. Fifty

years later the Encyclopedia Americana was published.

At around the same

time, the first daily and weekly newspapers began as a means for writers to

share their ideas. More and more people learned to read, so the demand for

written material increased. It was not uncommon for a group of working class

people to gather together in order to read pamphlets and newspapers aloud to

each other and debate the ideas presented. Soon people began to gather in

coffeehouses to argue and discuss politics, recent scientific developments, and

anything else of interest. The Age of Reason reached into many homes throughout

Europe in this way.

New ideas come before changes in society. The

concept of “progress” which came about during the Enlightenment meant that

people looked into the future rather than into the past. As ideas changed and

people broke free from old, rigid thought, the way was opened for even bigger

changes to come. People had higher expectations for a good quality of life, but

monarchs clung fast to their power. The discrepancy between people’s dreams and

ideals on one hand, and the reality of poverty and powerlessness on the other,

led to enormous struggles.