Spanish-American War

Spanish-American

War, brief war that the United States waged against Spain in 1898. Actual

hostilities in the war lasted less than four months, from April 25 to August 12,

1898. Most of the fighting occurred in or near the Spanish colonial possessions

of Cuba and the Philippines, nearly halfway around the world from each other. In

both theaters the decisive military event was the complete destruction of a

Spanish naval squadron by a vastly superior U.S. fleet. These victories left the

Spanish land forces isolated from their homeland and, after brief resistance,

brought about their surrender to U.S. military forces. The defeat marked the end

of Spain’s colonial empire and the rise of the United States as a global

military power.

Spanish-American

War, brief war that the United States waged against Spain in 1898. Actual

hostilities in the war lasted less than four months, from April 25 to August 12,

1898. Most of the fighting occurred in or near the Spanish colonial possessions

of Cuba and the Philippines, nearly halfway around the world from each other. In

both theaters the decisive military event was the complete destruction of a

Spanish naval squadron by a vastly superior U.S. fleet. These victories left the

Spanish land forces isolated from their homeland and, after brief resistance,

brought about their surrender to U.S. military forces. The defeat marked the end

of Spain’s colonial empire and the rise of the United States as a global

military power.

A number of factors contributed

to the U.S. decision to go to war against Spain. These included the Cuban

struggle for independence, American imperialism, and the sinking of the U.S.

warship Maine.

A number of factors contributed

to the U.S. decision to go to war against Spain. These included the Cuban

struggle for independence, American imperialism, and the sinking of the U.S.

warship Maine.

The war grew out of the Cuban struggle for

independence. Since the early years of the 19th century, many Americans had

watched with sympathy the series of revolutions that ended Spanish authority

throughout South America, Central America, and Mexico (see Latin American

Independence). Many people in the United States were irritated that the Spanish

flag continued to fly in Cuba and Puerto Rico. The brutality with which Spain

put down Cuban demands for a degree of local autonomy and personal liberty

aroused both sympathy and anger. Support for the cause of Cuban independence had

deep historical roots in the United States, and this cause became the stated

objective of the war.

The Cubans revolted in 1895 under the inspired

leadership of Cuban patriot Jose Martí. The revolt was prompted by the failure

of the Spanish government to institute reforms it had promised the Cuban people

at the conclusion of a rebellion against Spanish rule known as the Ten Years’

War (1868-1878). To put down the 1895 rebellion, the Spanish government poured

more than 100,000 troops into the island. General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau,

known as the "Butcher" for his ruthless suppression of earlier revolts, was sent

to the island as captain general and military governor. He immediately rounded

up the peasant population and put them in concentration camps in or near

garrison towns. Thousands died of starvation and disease.

The brutality of "Butcher" Weyler aroused great

indignation in the United States. The general anger was exploited by sensational

press reports, which exaggerated even Weyler’s ruthlessness. In 1897 the Spanish

government became alarmed at the belligerent tone of public opinion in the

United States. Weyler was recalled, and overtures were made to the rebels. The

rebels rejected an offer of autonomy, however, and were determined to fight for

complete independence.

An important factor in

the U.S. decision to go to war was the growing imperialism of the United States,

as seen in the mounting efforts to extend American influence overseas. The

increasingly aggressive behavior of the United States was often justified by

references to Manifest Destiny, a belief that territorial expansion by the

United States was both inevitable and divinely ordained; this belief enjoyed

widespread support among U.S. citizens and politicians in the 19th century.

Manifest Destiny was promoted by the publishers of several prominent U.S.

newspapers, particularly William Randolph Hearst, the publisher of TheNew

York Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher of the

New York World.

An important factor in

the U.S. decision to go to war was the growing imperialism of the United States,

as seen in the mounting efforts to extend American influence overseas. The

increasingly aggressive behavior of the United States was often justified by

references to Manifest Destiny, a belief that territorial expansion by the

United States was both inevitable and divinely ordained; this belief enjoyed

widespread support among U.S. citizens and politicians in the 19th century.

Manifest Destiny was promoted by the publishers of several prominent U.S.

newspapers, particularly William Randolph Hearst, the publisher of TheNew

York Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher of the

New York World.

Their newspapers published a steady stream of

sensational stories about alleged atrocities committed by the Spanish in Cuba,

calling for the United States to intervene on the side of the Cubans. The spirit

of imperialism growing in the United States—fueled by supporters of Manifest

Destiny—led many Americans to believe that the United States needed to take

aggressive steps, both economically and militarily, to establish itself as a

true world power.

| C |

|

The

Sinking of the Maine |

In January 1898 serious disorder broke out in Havana, Cuba. The U.S. consul

general in the city asked that a U.S. warship be sent to the harbor to protect

U.S. citizens and property. The second-class battleship Maine was ordered

to Havana. On the night of February 15 the Maine was destroyed by an

underwater explosion while at anchor in Havana harbor and 266 officers and men

were lost. Exactly how and why the explosion occurred could not be determined at

the time, but many people in the United States believed the Spanairds were

responsible. "Remember the Maine!" became the national battle cry

overnight. A U.S. Navy study published in 1976 suggested that spontaneous

combustion in the ship’s coal bunkers caused the explosion.

U.S. President William McKinley had hoped to avoid war with Spain, but he was

swept along on the wave of national feeling in support of war. On April 11 he

sent a message to Congress asking for the authority to put an end to the

fighting in Cuba. The fact that he knew Spain had just ordered an armistice was

barely touched on in the message. On April 19 a joint resolution of the two

houses of Congress gave him the authority to intervene. On April 22 the North

Atlantic Squadron was ordered to blockade Cuba. A declaration of war on April 25

was hardly more than a formality. Congressional resolutions affirmed Cuban

independence and stated that the United States was not acting to secure an

empire.

At the beginning of the war there were nearly 200,000

Spanish troops in Cuba. About 125,000 were regulars and the remainder were local

volunteers. The regulars were well-trained men armed with up-to-date magazine

rifles. The bulk of the troops were stationed at Havana in the western part of

the island. Havana was linked by rail with the port of Cienfuegos on the

south-central coast. The remainder of the island was accessible from Havana only

by sea or by very mediocre roads, and the countryside swarmed with Cuban

insurgents.

In contrast, the U.S. Regular Army had a total strength

of some 25,000. These troops were scattered in small posts throughout the

country. McKinley appealed initially for 125,000 volunteers, which he later

increased to 267,000, but these men could not be trained into reliable fighting

units for some time. Therefore, the cry of "On to Havana!" seemed unrealistic

indeed to Nelson A. Miles, the commanding general of the U.S. Army. Miles

proposed to concentrate all his regulars in one Army corps to take advantage of

any opportunity that might develop from the Navy’s operations.

The Navy’s basic job was

to blockade the island of Cuba. If the Spanish army could be cut off from

seaborne supplies from Spain, it could not maintain itself for long against the

Cuban insurgents, let alone prepare to fight the U.S. forces. To maintain a

successful blockade, the U.S. Navy would have to control the sea approaches to

Cuba. To accomplish this, the United States determined that the Spanish navy had

to be destroyed wherever it was found. Thus the U.S. war objectives were

broadened to include an attack on the Spanish naval base in the Philippines and

eventually the conquest of the Philippine islands themselves.

The Navy’s basic job was

to blockade the island of Cuba. If the Spanish army could be cut off from

seaborne supplies from Spain, it could not maintain itself for long against the

Cuban insurgents, let alone prepare to fight the U.S. forces. To maintain a

successful blockade, the U.S. Navy would have to control the sea approaches to

Cuba. To accomplish this, the United States determined that the Spanish navy had

to be destroyed wherever it was found. Thus the U.S. war objectives were

broadened to include an attack on the Spanish naval base in the Philippines and

eventually the conquest of the Philippine islands themselves.

On paper the Spanish navy was formidable, but in

reality many of its ships were not ready for sea. In the spring of 1898 a

squadron of four armored cruisers and three destroyers was the only Spanish

naval force in shape to proceed to the Caribbean. In actual fighting power, the

U.S. North Atlantic Squadron of four battleships and two armored cruisers was

overwhelmingly superior. Nevertheless, news that the Spanish squadron under

Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete was sailing westward across the Atlantic Ocean

from the Cape Verde Islands, off the western coast of Africa, caused a panic in

U.S coastal cities. Such a clamor arose for protection that the commander of the

North Atlantic Squadron, Rear Admiral William Thomas Sampson, was forced to

leave half of his squadron at Hampton Roads, Virginia, to discourage the Spanish

from bombarding U.S. seaports.

With his reduced forces, Sampson could not

simultaneously watch the two major Cuban ports of Cienfuegos and Santiago de

Cuba, located in southeastern Cuba. The Spanish squadron was prevented from

slipping into Cienfuegos harbor in May 1898 only by the belated arrival of a

squadron from Virginia. Sampson had finally pried this squadron loose after

Civil War monitors—heavily armored ships used for coastal bombardment—had been

substituted for the squadron’s ships in the harbors along the U.S. coast. These

communities were reassured by the monitors, although there was no ammunition

available for their muzzle-loaded guns. By June 1 Sampson’s fleet, reinforced by

the battleship Oregon, had blockaded Cervera’s Spanish squadron in the

port of Santiago de Cuba.

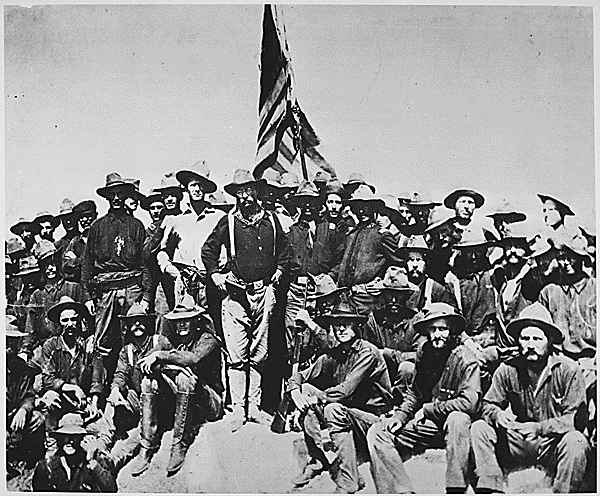

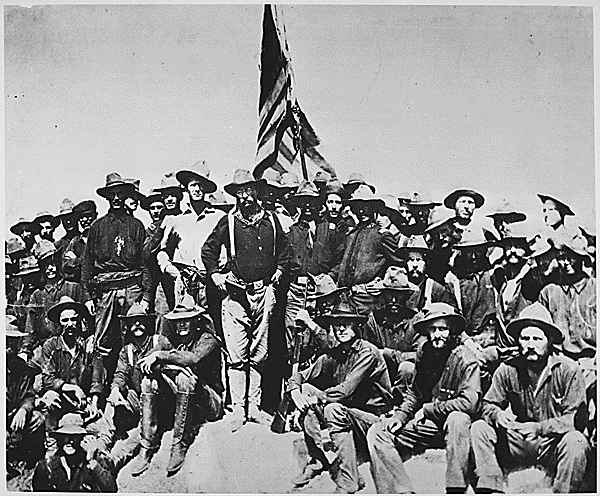

The U.S. Army had succeeded,

after extreme difficulty, in collecting some 16,500 men at Tampa, Florida. This

Fifth Army Corps was composed mainly of regulars, although there were also two

National Guard infantry regiments and a regiment of volunteer cavalry, called

the Rough Riders. This unit had been raised by Lieutenant Colonel (and future

U.S. president) Theodore Roosevelt and commanded at first by Colonel Leonard

Wood. When Wood was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in July 1898,

Roosevelt was made a colonel and assumed command of the cavalry regiment.

The U.S. Army had succeeded,

after extreme difficulty, in collecting some 16,500 men at Tampa, Florida. This

Fifth Army Corps was composed mainly of regulars, although there were also two

National Guard infantry regiments and a regiment of volunteer cavalry, called

the Rough Riders. This unit had been raised by Lieutenant Colonel (and future

U.S. president) Theodore Roosevelt and commanded at first by Colonel Leonard

Wood. When Wood was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in July 1898,

Roosevelt was made a colonel and assumed command of the cavalry regiment.

The Fifth Army Corps left Tampa without much military

order or discipline. Troops piled aboard the available ships in almost total

disregard of any loading plan, if indeed one existed. Drinking water had to be

rationed, the food was bad, and the congestion aboard the ships was incredible.

But on June 20 they arrived off the coast of Cuba. After some bitter discussion

with the civilian shipmasters, several of whom stoutly refused to bring their

ships close to this "enemy shore," men and supplies were bundled overboard into

boats. It took five days to get all of the Fifth Corps landed in Cuba.

The Rough Riders cavalry division, dismounted because

the horses had been left behind, was the first to land and it quickly pushed

ahead toward Santiago de Cuba. At Las Guásimas it fought the first land battle

of the war, a sharp skirmish in which a somewhat superior Spanish force was

driven from its positions. After several days of preparation, the U.S. division

launched a general attack on the morning of July 1. The attack, which was badly

coordinated, eventually took the Spanish positions at El Caney and on San Juan

Hill. More than 280 U.S. soldiers were killed and over 1500 wounded in the

fighting.

U.S. commanders were discouraged by the unexpectedly

heavy losses and did not immediately follow up with further attacks. The Spanish

captain general in Havana, however, was even more distraught. Convinced that

Santiago de Cuba could not be held, Ramon Blanco y Erenas telegraphed Admiral

Cervera, ordering him to take his ships to sea "to avoid being included in the

surrender."

| D |

|

Victory

in the Caribbean |

Cervera knew he was being ordered to certain

destruction but felt compelled to obey. He chose the morning of July 3 for a

hopeless but gallant escape attempt. The Spanish ships had to emerge from the

narrow harbor entrance one at a time, each in turn facing the concentrated fire

of the U.S. ships. Cervera’s flagship, Infanta Maria Teresa, led the

column and was taken under fire by the Iowa at 9:35 am. Within several

hours, all seven Spanish ships in the squadron had either been destroyed or

driven ashore.

The discrepancy in fighting power between the two

squadrons is underlined by the casualty figures. The Spaniards reported

casualties of 323 dead and 151 wounded. The Americans had 1 killed and 1

wounded. Cervera and more than 1700 of his officers and men became prisoners of

war. The battle marked the end of the Spanish Empire in the Americas.

The Spanish garrison at Santiago de Cuba surrendered on

July 17, after protracted negotiations and some intermittent shelling. On July

25, U.S. troops landed in Puerto Rico and took the island after encountering

only token resistance. Hostilities in the Caribbean were now at an end.

Two months before the U.S. victory in the Caribbean,

U.S. ships had already destroyed Spain’s naval forces in the Philippines. An

often debated question is why, in a war undertaken to end Spanish rule in Cuba,

a U.S. naval squadron should have been ordered to destroy a Spanish naval

squadron based in Manila, over 9000 miles away. A fairly prevalent theory

ascribes it to the so-called imperialism of Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt had become assistant secretary of the navy in

1897. His energy and enthusiasm had contributed notably to the readiness of the

U.S. Navy in the Spanish-American War. Late in 1897, before he resigned to

organize the Rough Riders, he had insisted on the appointment of Commodore

George Dewey to command the Asiatic Squadron. Dewey was an energetic and

determined officer, capable of swift and forceful action. On February 25, 1898,

Roosevelt sent Dewey a cable warning him of the need for vigorous action against

the Spanish squadron at Manila in case of war with Spain. However, it is

probable that Roosevelt was thinking simply of wiping out Spanish sea power

wherever it existed, rather than of American empire building. He was an ardent

disciple of Captain Alfred T. Mahan, whose views on the importance of control of

the seas were consistent with the actions Roosevelt took. However, Roosevelt’s

famous dispatch to the Asiatic Squadron had little bearing on Dewey’s actions.

The commodore had orders to attack the Spanish force in Manila when he left the

United States in December 1897, and he got specific orders to do this after war

broke out.

Dewey had his squadron concentrated in the British

harbor of Hong Kong when the war message arrived on April 24, 1898. He had four

steel cruisers—Olympia,Baltimore,Boston, and Raleigh—and two

seagoing gunboats—Concord and Petrel. The Spanish commander at

Manila, Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasaron, was as unprepared as the unfortunate

Cervera in Cuba. He had a total of seven ships. His flagship Reina Cristina

could be described as a cruiser. The other ships, except for a small, wooden

corvette, were steel or iron gunboats, mostly in poor repair.

Dewey left Hong Kong on April 25. When he arrived at

Manila Bay he faced several difficulties. He knew that the narrow entrance to

the bay was defended by heavy guns mounted on the islands of Corregidor and El

Fraile. He also had reason to believe that the channel was mined. Furthermore,

if any of his ships were to be severely damaged, he would have no means of

making repairs—he was 7000 miles from the nearest home port, and Hong Kong and

other neutral ports were now being closed to him.

None of these difficulties deterred Dewey, however, and

he led his darkened squadron into the harbor entrance. No mines exploded and

there was only scattered gunfire. As day broke on May 1, Dewey’s squadron was

well within Manila Bay. The city of Manila lay dead ahead, defended by batteries

that began long-range and ineffective firing at the U.S ships. Montojo’s

squadron, not Manila, was Dewey’s immediate objective. He bore away southward

toward the Spanish naval station at Cavite. Increasing daylight revealed the

Spanish warships at anchor there.

At 5:40 am, Dewey gave the order to fire. As in the

Caribbean, the battle was over in just a few hours, resulting in the destruction

of the Spanish squadron. Spanish casualties included at least 160 dead and 210

wounded. The U.S. forces had no fatal casualties. Only two officers and six men

were wounded, none seriously. None of the U.S. ships were badly damaged.

In spite of the victory, Dewey’s problems were just

beginning. He was holding Cavite with a few dozen Marines. In the city of

Manila, 12 miles away, there were 13,000 Spanish troops. A Filipino insurrection

was in progress against the Spanish, but the U.S. government could not make up

its mind whether to help the rebels or not. A further problem soon presented

itself. Britain, France, and Germany all sent warships to protect the interests

of their nationals in the Philippines. Behind these naval maneuvers was an

implied threat to move in if the United States itself did not take possession of

the Philippines.

Dewey threatened to bombard Manila if Spanish shore

batteries fired on his ships. When U.S. troops began to arrive on July 17, the

pressure eased rapidly. U.S. troop strength reached 8500 by the end of July, and

Dewey and the Army demanded the surrender of Manila on August 7. They then

arranged with the Spanish captain general to occupy key positions before the

Filipino insurgents did. The U.S. flag was hoisted over Manila on August 13.

Spain and the United States signed a peace treaty on

December 10, 1898, in Paris, France. It provided for Spanish withdrawal from Cuba, leaving the island under temporary U.S. occupation. Spain

was to retain liability for the Cuban debt. The United States did not push for

the annexation of Cuba because the Teller Amendment, passed when the U.S.

Congress declared war, prevented the United States from taking over Cuba. Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain to the United States, which

in turn paid Spain $20 million. In December 1898 the United States announced the

establishment of U.S. military rule in the Philippines.

withdrawal from Cuba, leaving the island under temporary U.S. occupation. Spain

was to retain liability for the Cuban debt. The United States did not push for

the annexation of Cuba because the Teller Amendment, passed when the U.S.

Congress declared war, prevented the United States from taking over Cuba. Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain to the United States, which

in turn paid Spain $20 million. In December 1898 the United States announced the

establishment of U.S. military rule in the Philippines.

The treaty and the U.S. occupation of the Philippines

encountered considerable opposition in the United States, prompting serious

questions about growing U.S. imperialism. Opponents argued that the region was

not vital to U.S. economic or military interests and that occupying the

Philippines violated the principles of democracy. Many prominent U.S.

citizens—including writer and satirist Mark Twain and business tycoon Andrew

Carnegie—criticized the annexation of the Philippines.

As justification for taking over the Philippines, it

was argued that the United States could not honorably hand the islands back to

Spain because Filipinos were "unprepared for self-government" and the islands

would simply fall prey to Germany or another power if U.S. forces left the

region. Pious talk about the United States’s duty to civilize so-called backward

races was accompanied by less altruistic mentions of the economic opportunities

that existed in Asia and the U.S. Navy’s desire for a base in the Philippines.

After an intense fight in the United States Senate, the

treaty was finally ratified on February 6, 1899, by a margin of just one vote.

The debate had revolved around whether the United States should annex and occupy

the Philippines or honor the Filipino declarations of independence and leave the

islands. The ratification of the treaty indicated that the United States was

committed to maintaining a military presence in the islands and that it would

oppose the Filipino independence movement.

| VII |

|

FILIPINO INSURRECTION |

Tensions arose between U.S. troops and Filipino

insurgents even before the treaty was ratified. Two days before the treaty was

signed, a U.S. sentry shot a Filipino soldier who had been trying to cross a

bridge in Manila. Hostilities soon escalated, marking the beginning of bloody

war between the United States and Filipino rebels that would last more than two

years. Although the Filipino troops were armed with old rifles and were badly

outmatched in open combat, they waged an effective form of guerrilla warfare,

using the country’s rough terrain to assist them in battling the better-armed

U.S. troops.

Between 200,000 and 600,000 Filipinos died during the

war against the United States. Most of them were civilians, killed more often by

famine and disease brought on by the warfare than by actual fighting. The war

destroyed livestock and interrupted farming activity, seriously reducing

agricultural output and creating food shortages. Fewer than 5000 U.S. soldiers

died during the conflict.

The insurrection was largely subdued by 1901, when

Filipino rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo surrendered, swore allegiance to the

United States, and called on other rebels to lay down their arms. U.S. President

Theodore Roosevelt declared an end to the war in 1902, but rebel resistance

continued in parts of the Philippines until 1903. The United States controlled

the Philippines until after World War II (1939-1945); the Philippines was

granted complete independence on July 4, 1946.

The peace treaty marked the end of Spain’s colonial

empire and the advent of the United States as a world power that would seek to

expand and protect its interests in Asia. Shortly before the treaty

negotiations, the annexation of Hawaii, which had been on hold for months, was

quietly accomplished.

In 1901 the U.S. Congress passed the Platt Amendment,

specifying the conditions under which the United States could intervene in the

internal affairs of newly independent Cuba. The amendment was included in the

Cuban constitution that was adopted later that year. Under that constitution,

Cuba also ceded to the United States territory to be used for U.S. naval

facilities (see Guantánamo Bay).

The Spanish-American War affected the United States in

a number of other ways. It firmly established the United States as a major

military power and illustrated the importance of a two-ocean navy to U.S.

military planners. The war helped speed the construction of the Panama Canal,

which was completed in 1914 and was seen as vital to linking the Atlantic and

Pacific oceans for U.S. commerce and military activities. The war also raised

the visibility of Theodore Roosevelt, who went on to become vice president in

1900 and president in 1901.

Spanish-American

War, brief war that the United States waged against Spain in 1898. Actual

hostilities in the war lasted less than four months, from April 25 to August 12,

1898. Most of the fighting occurred in or near the Spanish colonial possessions

of Cuba and the Philippines, nearly halfway around the world from each other. In

both theaters the decisive military event was the complete destruction of a

Spanish naval squadron by a vastly superior U.S. fleet. These victories left the

Spanish land forces isolated from their homeland and, after brief resistance,

brought about their surrender to U.S. military forces. The defeat marked the end

of Spain’s colonial empire and the rise of the United States as a global

military power.

Spanish-American

War, brief war that the United States waged against Spain in 1898. Actual

hostilities in the war lasted less than four months, from April 25 to August 12,

1898. Most of the fighting occurred in or near the Spanish colonial possessions

of Cuba and the Philippines, nearly halfway around the world from each other. In

both theaters the decisive military event was the complete destruction of a

Spanish naval squadron by a vastly superior U.S. fleet. These victories left the

Spanish land forces isolated from their homeland and, after brief resistance,

brought about their surrender to U.S. military forces. The defeat marked the end

of Spain’s colonial empire and the rise of the United States as a global

military power. A number of factors contributed

to the U.S. decision to go to war against Spain. These included the Cuban

struggle for independence, American imperialism, and the sinking of the U.S.

warship Maine.

A number of factors contributed

to the U.S. decision to go to war against Spain. These included the Cuban

struggle for independence, American imperialism, and the sinking of the U.S.

warship Maine. An important factor in

the U.S. decision to go to war was the growing imperialism of the United States,

as seen in the mounting efforts to extend American influence overseas. The

increasingly aggressive behavior of the United States was often justified by

references to Manifest Destiny, a belief that territorial expansion by the

United States was both inevitable and divinely ordained; this belief enjoyed

widespread support among U.S. citizens and politicians in the 19th century.

Manifest Destiny was promoted by the publishers of several prominent U.S.

newspapers, particularly William Randolph Hearst, the publisher of TheNew

York Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher of the

New York World.

An important factor in

the U.S. decision to go to war was the growing imperialism of the United States,

as seen in the mounting efforts to extend American influence overseas. The

increasingly aggressive behavior of the United States was often justified by

references to Manifest Destiny, a belief that territorial expansion by the

United States was both inevitable and divinely ordained; this belief enjoyed

widespread support among U.S. citizens and politicians in the 19th century.

Manifest Destiny was promoted by the publishers of several prominent U.S.

newspapers, particularly William Randolph Hearst, the publisher of TheNew

York Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer, the publisher of the

New York World. The Navy’s basic job was

to blockade the island of Cuba. If the Spanish army could be cut off from

seaborne supplies from Spain, it could not maintain itself for long against the

Cuban insurgents, let alone prepare to fight the U.S. forces. To maintain a

successful blockade, the U.S. Navy would have to control the sea approaches to

Cuba. To accomplish this, the United States determined that the Spanish navy had

to be destroyed wherever it was found. Thus the U.S. war objectives were

broadened to include an attack on the Spanish naval base in the Philippines and

eventually the conquest of the Philippine islands themselves.

The Navy’s basic job was

to blockade the island of Cuba. If the Spanish army could be cut off from

seaborne supplies from Spain, it could not maintain itself for long against the

Cuban insurgents, let alone prepare to fight the U.S. forces. To maintain a

successful blockade, the U.S. Navy would have to control the sea approaches to

Cuba. To accomplish this, the United States determined that the Spanish navy had

to be destroyed wherever it was found. Thus the U.S. war objectives were

broadened to include an attack on the Spanish naval base in the Philippines and

eventually the conquest of the Philippine islands themselves. The U.S. Army had succeeded,

after extreme difficulty, in collecting some 16,500 men at Tampa, Florida. This

Fifth Army Corps was composed mainly of regulars, although there were also two

National Guard infantry regiments and a regiment of volunteer cavalry, called

the Rough Riders. This unit had been raised by Lieutenant Colonel (and future

U.S. president) Theodore Roosevelt and commanded at first by Colonel Leonard

Wood. When Wood was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in July 1898,

Roosevelt was made a colonel and assumed command of the cavalry regiment.

The U.S. Army had succeeded,

after extreme difficulty, in collecting some 16,500 men at Tampa, Florida. This

Fifth Army Corps was composed mainly of regulars, although there were also two

National Guard infantry regiments and a regiment of volunteer cavalry, called

the Rough Riders. This unit had been raised by Lieutenant Colonel (and future

U.S. president) Theodore Roosevelt and commanded at first by Colonel Leonard

Wood. When Wood was appointed brigadier general of volunteers in July 1898,

Roosevelt was made a colonel and assumed command of the cavalry regiment. withdrawal from Cuba, leaving the island under temporary U.S. occupation. Spain

was to retain liability for the Cuban debt. The United States did not push for

the annexation of Cuba because the Teller Amendment, passed when the U.S.

Congress declared war, prevented the United States from taking over Cuba. Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain to the United States, which

in turn paid Spain $20 million. In December 1898 the United States announced the

establishment of U.S. military rule in the Philippines.

withdrawal from Cuba, leaving the island under temporary U.S. occupation. Spain

was to retain liability for the Cuban debt. The United States did not push for

the annexation of Cuba because the Teller Amendment, passed when the U.S.

Congress declared war, prevented the United States from taking over Cuba. Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the Philippines were ceded by Spain to the United States, which

in turn paid Spain $20 million. In December 1898 the United States announced the

establishment of U.S. military rule in the Philippines.