|

SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS Mexican Independence

Chieftains of

Mexican Independence

Miguel Gregorio

Antonio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y

Villaseñor

The stage for the upheaval and dissatisfaction that gave rise to Mexican independence was set by political and economic changes in Europe and its American colonies of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The French revolution and Napoleonic wars diverted attention of Spain from its colonies leaving a vacuum and increasing dissatisfaction and desire for local government. The forced removal of Ferdinand VII from the Spanish thrown and his replacement by Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon's brother presented opportunity for Mexican intelligentsia to promote independence in the name of the legitimate Spanish king. From its inception the colonial government of New Spain was dominated by Spanish born Peninsulares or Guachapins, who held most leadership positions in the church and government, in contrast to Mexican-born Criollos (Creoles) who were the ten to one majority. Neither Peninsulares or upper class Criollos desired to involve the masses of native Indians and mestizos in government or moves for local control. In 1808 the Peninsulares learned of Viceroy Jose de Iturrigaray’s intent to form a junta with Creole factions, a move that he thought might make him King of an independent Mexican kingdom. In an armed attack on the palace, Peninsulares arrested Iturrigaray and replaced him with puppet Pedro Garibay after which they carried out bloody reprisals against Criollos who were suspected of disloyalty. Although reform movements paused, political and economic instability in Europe continued as well as hardship and unrest in the Americas. One liberal organization that was forced underground was the Literary Club of Queretaro which formed for intellectual discussion, but in practice became a planning organization for revolution. Independence- and reform-oriented thinkers also began to consider enlisting the native Indian, mestizo and lower class masses in wresting control from the Peninsulares and in armed independence movements. Queretaro was an important agricultural region that had suffered extensively by economic stalemate and failure. An active member of the group was Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a well-educated liberal priest who questioned policies of the church including clerical celibacy, banning certain literature, infallibility of the pope and the virgin birth of Christ. Hidalgo became the curator of Dolores in 1803 with primarily an Indian congregation whose languages he spoke and to whom he administered practical skills of life as much as religious doctrine. In Queretaro, Hidalgo met Capt. Ignacio Allende, a revolutionary thinker in the Spanish army. In spring 1810, Allende and Hidalgo planned an uprising for December of the year that leaked out to Spanish authorities and their arrest was ordered. In September 1810, Father Hidalgo was forced to prematurely distribute the Grito de Delores to his parishoners and nearby residents which was an appeal for social and economic reform. With little organization and no training, essentially a mob of thousands of primarily Indians and mestizos overwhelmed royal forces in Guanajuato, and proceeded to murder and loot both Peninsulares, Criollos and other "whites" in their path. The force continued to Mexico City and defeated royalist on the outskirts, but did not enter and occupy the city after which the ragged revolutionary army returned home. Hidalgo and his Creole officers were later able to assemble an army of 80,000 by payment with looted Peninsulare gold and assets. Viceroy, Francisco Javier Venegas, and his soon to be successor Gen. Félix María Calleja responded to the insurgency with a vengeance and in January 1811 Hidalgo suffered a serious defeat outside Guadalajara where rebel forces were routed at Calderon Bridge. Bloody retaliation followed by mass executions of suspected rebel sympathizers by Spanish crown forces under Viceroy Calleja del Rey. Hidalgo and associates turned toward the northern provinces Nuevo Santander, Nuevo León, Coahuila and Texas for refuge where local sympathy for the rebellion and independence continued. Royalist forces in Nuevo Santander refused to fight against the insurgents as well as troops under Governor Manuel Antonio Cordero y Bustamante in Coahuila. As the royalist forces moved north to crush resistance, it was only in Coahuila and Texas that revolutionary events continued. On 21 March 1811, a periodic rebel turned loyalist, Ignacio Elizondo, ambushed Ignacio Allende, Father Hidalgo and associates at the Wells of Baján on the road to Monclova in Coahuila. Hidalgo and associates were captured and executed in Chihuahua. sdct Hidalgo Archives: Selected Original Documents Father Hidalgo's Grito de Delores

"animated them to begin vigorously the enterprise of our Independence, and raising his voice with great valor, said: Long Live Our Lady of Guadalupe, Long Live Independence." Pedro Garcia, who probably did not join the insurgent army until it passed through his native San Miguel el Grande, reported that after all the events of the night had occurred people began to assemble for early morning Mass at the parish church. They found no one there to conduct the service. Having heard rumors of the Cura's midnight activities, a large number of parishioners gathered in front of Hidalgo's house. The priest, seeing it was time to explain his actions and gain more adherents, came out of the entrance hall and said,

Juan de Aldama's account of the Grito was recorded only a few months after the event. His version indicates some practical considerations but omits mention of any climactic conclusion to Hidalgo's speech. At about eight o'clock in the morning

We know from Hidalgo's own statements that he was convinced from the start that independence should be the goal of the rebellion. This conviction was known by Captain Arias before the Grito, for Juan Ochoa wrote on September 11 that

Nevertheless, it is extremely doubtful that Hidalgo repudiated the King and raised the cry of "Long Live Independence!" Aldama's version of Hidalgo's address is the most reliable. In view of the early insistence by insurgent proclamations that the Revolt was to protect the Kingdom from the French and that all was being carried out in the name of Ferdinand VII, it seems most unlikely that Hidalgo would have rejected this approach at the beginning---the most crucial and vulnerable moment of any rebellion. The fear of the French and the good name of Ferdinand were successful devices for arousing popular enthusiasm. Even Hidalgo with all his impetuosity was not so rash as to risk failure by making the wrong appeal to the masses. He probably recalled Pedro Septien's reminder, reported in Allende's letter of August 31, that "the Indians were indifferent to the word liberty." The most convincing argument against the use of "Independence" in the Grito lies in the fact that Hidalgo and the others were successful in capturing Dolores and raising an initial army of between 500 and 800 men. If such success had been achieved in the name of independence, why did revolutionary propaganda for the next two months rely so heavily on the promise to support Ferdinand VII? What Hidalgo said in Dolores will probably never be known. It is reasonable to suppose, however, that the climax of his speech included one or all of the following:

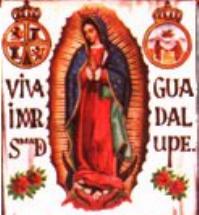

The plans of the Valladolid Conspiracy provided a precedent for abolition of the tribute and outlaw of slavery and the caste system to attract the Indians ["naturals" or American natives]. We may be almost certain that Hidalgo promised its end (see Hidalgo's Edict Against Slavery). Exploitation of the French threat led naturally to a declaration in defense of religion, another subject of mass appeal. Many believed that Spanish authorities had accepted the anti-Catholic views of the French Revolution. The incorporation of the Virgin of Guadalupe as the principal standard of the rebels took place later in the same day. The cry of "Long Live Our Lady of Guadalupe" was probably not raised until then.

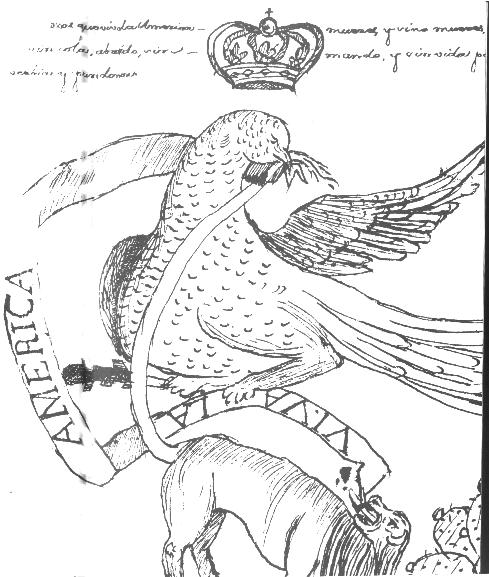

"If you confess that America lives, you die, and if you do not die, you will be shorn of your tail, left abject, and stripped of your dominion, pride and honor." The cartoon is thought to depict the intellectual political thinking of the criollos insurgents at a time when most of European Spain was under French domination. There was no way that Spain would admit French influence over New Spain (America). If America separate from France was acknowledged, then French domination of European Spain is admitted. If Spain does not recognize New Spanish America and hold her, then Mexico will fill the gap. The crown above the eagle is thought to suggest that the conspirators objective was autonomy under the monarchy. sdct

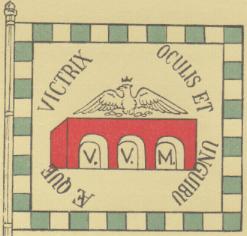

(Banner at top right is the Battle Flag of Morelos forces inscribed in Latin "She conquers equally with her eyes and her talons.") After Hidalgo’s death, mestizo parish priest José María Morelos y Pavon was able to organize a number of the independent chieftains across Mexico, established a Congress which created a declaration of rights and independence from Spain under King Ferdinand VII and a Constitution (See Sentimientos de la Nacion) which included abolition of slavery and equality of classes (See Decree Concerning Castes). Morelos, José María Cos and José María Liceaga served as an Executive Junta (Poder Ejecutivo). Father Morelos was captured while attempting to escort the Congress from Vallilodad to join the troops of Gen. Manuel Mier y Terán in Puebla. He is said to have diverted the royal troops attention to a small diversionary force of which he was at the head from the Congress. After capture, Morelos was tried by both military tribunals and the Inquisition. He was defrocked/degraded and executed in December 1815. Gen. Manuel Mier y Terán inherited the leadership of the movement after the death of Morelos, but was unable to unite it. Diverse and independent guerrilla and militia with various motives and loyalties, hostile to the established order continued throughout the provinces including Texas. This dissension facilitated Viceroy Calleja's forces to sequentially crush or keep under control the fragmented movement. The subsequent Viceroy Juan Ruiz de Apodaca took a conciliatory stance offering amnesty to former rebels, which according to some historians was much more successful in pacification than the bloody reprisals of Calleja. Until 1820, any organized movement for Mexican independence, except the filibustering action of Xavier Mina and others primarily based in Texas, lay dormant. sdct Morelos Archives: Selected Original Documents

With these developments, Texas became part of an independent Mexico and the "Lone Star" of hope for a second democratic, multi-cultural Federal Republic in America. SONS OF DEWITT COLONY TEXAS |

From The Hidalgo Revolt by Hugh

Hamill. At the core of Mexican patriotism is Hidalgo's Grito

de Dolores. Every year, on the night of September 15-16, the President of

the Republic "reenacts" the Grito on a balcony of the National Palace as

the climax of the Independence Day celebrations. To do this with

historical accuracy is well-nigh impossible, for no one knows precisely

what Hidalgo said. The three principal contemporary reports fail to agree.

Sotelo's account, the most confused and least authoritative, stated that

the Grito was a short speech made from the window of the priest's house to

the first group of followers who assembled before dawn. Hidalgo

From The Hidalgo Revolt by Hugh

Hamill. At the core of Mexican patriotism is Hidalgo's Grito

de Dolores. Every year, on the night of September 15-16, the President of

the Republic "reenacts" the Grito on a balcony of the National Palace as

the climax of the Independence Day celebrations. To do this with

historical accuracy is well-nigh impossible, for no one knows precisely

what Hidalgo said. The three principal contemporary reports fail to agree.

Sotelo's account, the most confused and least authoritative, stated that

the Grito was a short speech made from the window of the priest's house to

the first group of followers who assembled before dawn. Hidalgo

Among the Queretaro Conspirators was a grocer named Epigmenio

Gonzales (1778-1858) whose store and personal effects were seized upon

discovery of the Hidalgo conspiracy in fall 1810. The sketch at left was

among Gonzales's papers which is a cartoon using the historic Aztec symbol

of an eagle perched on cactus. Instead of the snake, the tail of the

Spanish lion is in the Mexican eagle's mouth. The lion cries "Long

Live America." The caption at top reads

Among the Queretaro Conspirators was a grocer named Epigmenio

Gonzales (1778-1858) whose store and personal effects were seized upon

discovery of the Hidalgo conspiracy in fall 1810. The sketch at left was

among Gonzales's papers which is a cartoon using the historic Aztec symbol

of an eagle perched on cactus. Instead of the snake, the tail of the

Spanish lion is in the Mexican eagle's mouth. The lion cries "Long

Live America." The caption at top reads

If Morelos had lived to

the year 1821, Iturbide would not have been able to take control of

the national insurrection; and the nation would not have passed

through a half century of shameful and bloody revolution which

caused it to lose half of its territory. Today it would be the

powerful republic which we would have expected from seventy years of

development initiated by the courage, the abnegation, prudence, and

political skill, of which that extraordinary man was the

model--written by Porfirio Diaz in 1891 in the album of

tributes to Morelos in Casa de Morelos in

Morelia

If Morelos had lived to

the year 1821, Iturbide would not have been able to take control of

the national insurrection; and the nation would not have passed

through a half century of shameful and bloody revolution which

caused it to lose half of its territory. Today it would be the

powerful republic which we would have expected from seventy years of

development initiated by the courage, the abnegation, prudence, and

political skill, of which that extraordinary man was the

model--written by Porfirio Diaz in 1891 in the album of

tributes to Morelos in Casa de Morelos in

Morelia

Motivated by events in Spain which forced post-Napoleonic and

tyrannical King Ferdinand VII to restore elements of constitutional

government (Constitution of 1812), former Royalist commander

Agustín Iturbide, a mestizo accepted as a

criollo who opposed the insurgent approach to independence, formed a junta

with revolutionary Vicente Guerro to engineer Mexican independence in

1821. He was first groomed by church officials, plotters of the Church of

Profesa, whose power and wealth was threatened by liberal Spanish reforms.

Independence and maintenance of their local authority in Mexico was their

only recourse. They persuaded the Viceroy to appoint Iturbide head of the

force preparing to destroy Vicente Guerrero's stronghold, one of the most

consistent and most active resistance leader from the time of Morelos'

death. Instead of a battle and backed by other conservative and liberal

factions in Mexico, they formulated and announced on 24 Feb 1821 the

Motivated by events in Spain which forced post-Napoleonic and

tyrannical King Ferdinand VII to restore elements of constitutional

government (Constitution of 1812), former Royalist commander

Agustín Iturbide, a mestizo accepted as a

criollo who opposed the insurgent approach to independence, formed a junta

with revolutionary Vicente Guerro to engineer Mexican independence in

1821. He was first groomed by church officials, plotters of the Church of

Profesa, whose power and wealth was threatened by liberal Spanish reforms.

Independence and maintenance of their local authority in Mexico was their

only recourse. They persuaded the Viceroy to appoint Iturbide head of the

force preparing to destroy Vicente Guerrero's stronghold, one of the most

consistent and most active resistance leader from the time of Morelos'

death. Instead of a battle and backed by other conservative and liberal

factions in Mexico, they formulated and announced on 24 Feb 1821 the